Thursday, 16 July 2020

Finding the artist behind a set of engravings

Gers Gascogne, from France, sells on 17 July 2020 a series of 12 "old" engravings showing the months, in 4 frames, with an estimate of 40 to 60 Euro.

This seemed cheap, so I tried to find who the artists were behind this series (both the designer and the engraver). Sadly, the images are rather blurry, so I had trouble deciphering the texts on the engravings.

Only for the January example was a somewhat better example available, which seemed to show that no indication of engraver or publisher was visible on the engraving. But it made the inscription readable, and thus searchable.

The line "Lignis instrue focum" appears on an engraving of January by Lucas van Doetecum. Wow, good news, the van Doetecums were some of the most important engravers of the late 16th century, working for Hieronymus Cox and e.g. engraving a lot of works of Pieter Bruegel. Google linked me to the Met Museum, which owns a copy and described the inscription. Too bad, no image available. The dimensions seem wrong though, 26 by 35 cm vs. the 18 by 23 for the lot for sale.

I also found another set of engravings with the same inscription, this time at the Escorial, by Petrus van der Borcht. Again, no image... Size was 20 by 24, so a lot closer to the ones here, and a possible match. Oh no, they say the inscription on theirs is "Januar.", while we are looking for "Januarius"...

But the same site also has a set of 12 by Van Doetecum, and this time the dimensions are 20 by 24cm, so perhaps this is the one we are looking for? But again the inscription is "Ianuar.", not "Ianuarius".

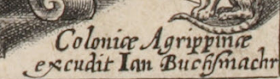

Which brings us to the final of the just four Google hits for this three-word search: the graphical collection of the Milan Library. Clicking through brought me a dedicated page for this very engraving, with an image. Finally, success! It's not a complete match though, as this one has a location and artist mentioned: Cologne (Coloniae Agrippinae), and "Ian Buchsmachr".

Not a name I'm familiar with, and one for which very little information is available it seems. An old book on German engraving claimed that this set of 12 months was made by Mathias Quad. Another book, from 1895 this time, claims that one set can be found in Dresden and is there attributed to Adriaen Collaert. I can't find any recent images of works by either Quad or Collaert showing these engravings though. I did learn that Buchsmachr is better known as Johann Bussemacher, engraver and printer (mainly of maps, often engraved by Quad) active around 1600 in Cologne.

So, now we know that some (original? later?) version was printed in Germany around 1600. Which tells us nothing about the one for sale here, nor about who designed and engraved it originally (if not Bussemacher).

And then a long and rather frustrating image search followed, having exhausted all text researches. I'll not tire you with all things I didn't found, let it suffice that in the end I came across a completely different artist and region: Étienne Delaune (1518-1583). He made multiple series of the 12 months, this is the first one from 1561.

But (and with these engravings, the number of "buts"has been impressive), the ones for sale are not the original ones by Delaune, or at least not the first state, which had a more "handwritten" lettering, and no numbers to the right of the months.

A version which looks (from the very small pictures) to be the same as the one for sale here (though obviously in better condition) was sold at Bassenge in 2014 for 1,800€, wow! Interestingly, they reference some literature about these engravings, which give Gerard van Groeninge as a possible designer, and link them to the series of 12 months by Van Doetecum, which was the first thing I encountered in my search! The circle is round after all, even though the ones for sale are sadly not the Van Doetecum works, nor the first state of the Delaune ones.

So at the end of all this, I know who the original engraver of these 12 works was, although I don't know yet who was the artist of the designs; I still haven't found any other copies of the versions I am researching though, only two others sets (the original set in two states, and the Cologne version), which is a bit frustrating. Because they don't bear the name of the engraver or publisher, they probably are usually catalogued as anonymous or with a wrong attribution.

If they were in good condition, I would have bid on them, but as it stands, and taking into account shipping costs, I'll pass, though with some regret.

UPDATE: sold for 1,200 Euro, 30 times the estimate!

The same auction has some other lots which are mainly interesting if you can pick them up yourselves, avoiding shipping and handling costs.

Lot 75 is an engraving with an "undecipherable" signature, which is a 1648 work "Pater Familias" by Adriaen van Ostade. Looks like a later copy though, but at 5 to 8 Euro you can't really go wrong here.

UPDATE: sold for 55 Euro, a much more logical price.

Lot 105 is a Picasso Domino, estimated at 8 to 15 Euro. This was originally a limited edition (some 2000 copies) from 1960,in which case it is worth around 200 to 300 Euro. Later (post-1985) versions exist, with a CE mark and without certificate, and these are worth around 50 Euro. A good buy in any case.

UPDATE; sold for 70 Euro.

Monday, 13 July 2020

Johanna van Frijtom

Johanna van Frijtom (1662-1740) (also: Jannetje Frijtom) was one of the rare female painters in the seventeenth century. Born and living in Delft, she was the daughter of (porcelain) painter Frederick van Frijtom and Pauline "Lijntje" Stevens. Only some 5 paintings by Johanna are attested, including one with card players in a collection in Stockholm, and a portrait of a lady which was sold in 1830 in Brussels (and which may be the same as a self portrait in the inventory of her father), and a portrait of her father?

The other two are both depictions of Vertumnus and Pomona, one in the City Museum "Het Prinsenhof" in Delft, and the one for sale here. The one in Delft (image via the RKD) is slightly larger (60 by 55 instead of 56 by 47).

The work in Delft (and thus also the one for sale now) is clearly inspired by a work by Thomas van der Wilt (or the 1688 engraving by Jan Brouwer, shown from the Rijksmuseum). Not only the two persons, but also her walking stick, the stone vase, the bird, ...

According to the "Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon Nederland", the version of the Vertumnus for sale now was sold in 1983 as a work by her father.

Invaluable shows that it was offered for sale at Cheffin's in 2009, with an estimate of £3,000 to £5,000 at the time, but remained unsold. It was then in a "private collection, Newcastle", and the current sale is in Newcastle... It is not clear whether they had a much better photograph, or whether the painting has considerably deteriorated in the last 10 years. In either case you will get a better painting (now of after cleaning) than the auction seems to show.

In itself, it is a reasonable but far from brilliant painting, based on (but not purely copied from) an engraving: even then, £400 would be cheap, but not by much.

However, as a signed work by one of the few female painters active in the Netherlands (or anywhere for that matter) around 1700, it is very cheap, and a unique chance to acquire a work by her. It is not at the level of works by Ruysch, Peeters, Leyster or Wautier, but most of us can't afford paintings by these anyway. It should fetch at least a few thousands pounds if enough collectors and museums realise its rarity.

The work in Delft (and thus also the one for sale now) is clearly inspired by a work by Thomas van der Wilt (or the 1688 engraving by Jan Brouwer, shown from the Rijksmuseum). Not only the two persons, but also her walking stick, the stone vase, the bird, ...

According to the "Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon Nederland", the version of the Vertumnus for sale now was sold in 1983 as a work by her father.

Invaluable shows that it was offered for sale at Cheffin's in 2009, with an estimate of £3,000 to £5,000 at the time, but remained unsold. It was then in a "private collection, Newcastle", and the current sale is in Newcastle... It is not clear whether they had a much better photograph, or whether the painting has considerably deteriorated in the last 10 years. In either case you will get a better painting (now of after cleaning) than the auction seems to show.

In itself, it is a reasonable but far from brilliant painting, based on (but not purely copied from) an engraving: even then, £400 would be cheap, but not by much.

However, as a signed work by one of the few female painters active in the Netherlands (or anywhere for that matter) around 1700, it is very cheap, and a unique chance to acquire a work by her. It is not at the level of works by Ruysch, Peeters, Leyster or Wautier, but most of us can't afford paintings by these anyway. It should fetch at least a few thousands pounds if enough collectors and museums realise its rarity.

Thursday, 14 May 2020

Finding the identity of the sitter and the provenance of a portrait from 1560

Beurret & Bailly - Galerie Widmer, from Switzerland, sells on 24 June 2020 a "Circle of Nicolas de Neufchâtel" portrait of a man, dated 1560, estimated at 4,000 to 6,000 Swiss Francs.

The portrait has an indication "Aetatis Suae XXXIII" (second image is same as first one, but adjusted for readability).

At the bottom, the sitter is writing a text, which (once one finds a picture with enough detail, and once it is turned upside down) is surprisingly readable. Even so, the signature is hard to decipher.

The text reads, as far as I can tell:

"* Espor me conforte *"

"en comfortant en tant entierement"

"en sien esivent(?) tant puisant"

"atonieme(?) inevemse(?) fortneta(?) et neve(?)"

"afin que glerifit(?) son intoneta(?)"

"nom en anga(?)" "1560"

"D. Aellaein(?)"

The text seems to be in French, but there is too much that I can't decipher to really give a translation of it.

The only things that made a search possible were the year (1560) and the title or motto at the top of the page. I hadn't much hope, but was pleasantly surprised when I found the following in, of all places, the library of the Theological Seminary of Princeton University; "Anna Maria van Schurman" by Dr. G. D. J. Schotel, preacher in Tilburg (the Netherlands), published in 1853.

On page 47, as a footnote to the first addendum, I read the following text:

Translated this gives:

"The first Alewijn was Dirck Alewijn, married to Cornelia Cannius, whose portrait, with a writing pen in the hand and a four-lined poem in front of him, topped with; Espor me conforte, still resides with the Alewijn family. This portrait shows him aged 33 and is dated to 1560."

Which is a perfect match, down to the name of the sitter (Alewijn) and the signature (Aellaein).

So, how did this painting end up in Switzerland instead of being in the hands of the family? Some nefarious WWII related story? Apparently not, as the article "De familieportretten der Alewijns" ("the family portraits of the Alewijns") in "De Gids" (kind of a literary journal) in 1886 described "de onlangs verkochte verzameling Alewijn" ("the recently sold collection Alewijn") as one of those collections which hadn't been "polluted" by unrelared portraits through the centuries.

Niet langs kunstmatigen weg ontstaan, maar ongeschonden overleverende aan de nakomelingschap wat in den loop der eeuwen op ongezochte wijze was bijeengekomen, toont zij ons in allen eenvoud en natuurlijkheid een belangwekkende reeks van Hollandsche burgers, die wij, even als wij ze door de verschillende generatiën hunner genealogie kunnen volgen, op paneel of doek zien gebracht door de verschillende kunstgeneratiën van schilders, die we van de onbekende meesters der zestiende eeuw zien opklimmen tot Moreelse, de Keyser en Santvoort, om, langs Maes, op de Musscher, op Quinkhard en op nog minder, te dalen. In deze geregelde volledigheid zonder overlading, overtreft de galerij Alewijn de meeste familie-galerijen die in ons land in den laatsten tijd, hetzij onder den hamer gekomen, hetzij door de zorg des laatsten eigenaars in hun geheel aan de openbare Musea toevertrouwd zijn.

Translation:

"Not created through an artificial way, but transmitting unchanged to the heirs whatever had come together throughout the centuries, it shows us in all simplicity and naturally an important series of Dutch citizens, which we, just like we can follow them through different generations of their family tree, see brought on panel or canvas by the different art generations of painters, who we see climbing from the unknown masters of the 16th century to Moreelse, de Keyser and Santvoort, and then, by Maes, see descending at De Musscher, at Quinkhard, and even lower. In this well-ruled completeness without overabundance, the gallery Alewijn surpasses most family galleries which in this country have recently been sold at auction or have been entrusted completely to public museums by the care of the last owners."

Rather flowery language, but it tells us that the paintings were at the time all considered to be true Alewijn portraits (good), that the 16th century ones were by unknown masters (ah, too bad), and that the collection also contained works by or attributed to major and minor masters.

The portrait has an indication "Aetatis Suae XXXIII" (second image is same as first one, but adjusted for readability).

At the bottom, the sitter is writing a text, which (once one finds a picture with enough detail, and once it is turned upside down) is surprisingly readable. Even so, the signature is hard to decipher.

The text reads, as far as I can tell:

"* Espor me conforte *"

"en comfortant en tant entierement"

"en sien esivent(?) tant puisant"

"atonieme(?) inevemse(?) fortneta(?) et neve(?)"

"afin que glerifit(?) son intoneta(?)"

"nom en anga(?)" "1560"

"D. Aellaein(?)"

The text seems to be in French, but there is too much that I can't decipher to really give a translation of it.

The only things that made a search possible were the year (1560) and the title or motto at the top of the page. I hadn't much hope, but was pleasantly surprised when I found the following in, of all places, the library of the Theological Seminary of Princeton University; "Anna Maria van Schurman" by Dr. G. D. J. Schotel, preacher in Tilburg (the Netherlands), published in 1853.

On page 47, as a footnote to the first addendum, I read the following text:

Translated this gives:

"The first Alewijn was Dirck Alewijn, married to Cornelia Cannius, whose portrait, with a writing pen in the hand and a four-lined poem in front of him, topped with; Espor me conforte, still resides with the Alewijn family. This portrait shows him aged 33 and is dated to 1560."

Which is a perfect match, down to the name of the sitter (Alewijn) and the signature (Aellaein).

So, how did this painting end up in Switzerland instead of being in the hands of the family? Some nefarious WWII related story? Apparently not, as the article "De familieportretten der Alewijns" ("the family portraits of the Alewijns") in "De Gids" (kind of a literary journal) in 1886 described "de onlangs verkochte verzameling Alewijn" ("the recently sold collection Alewijn") as one of those collections which hadn't been "polluted" by unrelared portraits through the centuries.

Niet langs kunstmatigen weg ontstaan, maar ongeschonden overleverende aan de nakomelingschap wat in den loop der eeuwen op ongezochte wijze was bijeengekomen, toont zij ons in allen eenvoud en natuurlijkheid een belangwekkende reeks van Hollandsche burgers, die wij, even als wij ze door de verschillende generatiën hunner genealogie kunnen volgen, op paneel of doek zien gebracht door de verschillende kunstgeneratiën van schilders, die we van de onbekende meesters der zestiende eeuw zien opklimmen tot Moreelse, de Keyser en Santvoort, om, langs Maes, op de Musscher, op Quinkhard en op nog minder, te dalen. In deze geregelde volledigheid zonder overlading, overtreft de galerij Alewijn de meeste familie-galerijen die in ons land in den laatsten tijd, hetzij onder den hamer gekomen, hetzij door de zorg des laatsten eigenaars in hun geheel aan de openbare Musea toevertrouwd zijn.

Translation:

"Not created through an artificial way, but transmitting unchanged to the heirs whatever had come together throughout the centuries, it shows us in all simplicity and naturally an important series of Dutch citizens, which we, just like we can follow them through different generations of their family tree, see brought on panel or canvas by the different art generations of painters, who we see climbing from the unknown masters of the 16th century to Moreelse, de Keyser and Santvoort, and then, by Maes, see descending at De Musscher, at Quinkhard, and even lower. In this well-ruled completeness without overabundance, the gallery Alewijn surpasses most family galleries which in this country have recently been sold at auction or have been entrusted completely to public museums by the care of the last owners."

Rather flowery language, but it tells us that the paintings were at the time all considered to be true Alewijn portraits (good), that the 16th century ones were by unknown masters (ah, too bad), and that the collection also contained works by or attributed to major and minor masters.

RKD: Cornelis Van der Voort, 1617, portrait of Dirck Alewijn (presumably a nephew of the sitter in the portrait for sale): current whereabouts unknown. Was attributed to Moreelse at the 1885 sale.

The same sitter also returns in a drawing by Wallerant Vaillant, together with a pendant showing his wife Maria Schurman

Rijksmuseum: Paulus Moreelse, portrait of Reinier Pauw, husband of Clara Alewijn, 1625 (the portrait of his wife (also by Moreelse) was lost in a fire in 1906)

In The Hague, at the "Hoge Raad van de Adel", are kept two paintings by presumably Nicolaes Pickenoy (but earlier attributed to Thomas De Keyser), showing Dirck de Graeff and Eva Bicker, dating to 1630. After the death of De Graeff, Bicker married into the Alewijn family, and the images entered the family gallery.

Portraits of Martinus and Clara Alewijn, 1644, by Dirck Dircks van Santvoort, now in the Rijksmuseum

Norton Simon Museum: Dirck Alewijn and his wife Agatha Bicker, by Nicolaes Maes, 1675

So, we have now identified some of the paintings by the most important artists mentioned in that 1885 text about the gallery and its sale; online, one can find even more paintings and drawings of the family by Vaillant, Santvoort, ... and later, lesser artists. This has also shown how the Alewijn family was one of the most important families in Amsterdam at the time, marrying with other prominent families like the Bickers, Pauw, De Graeff, ...

The text from "De Gids", already quoted above regarding the gallery in general, then describes in more detail the painting for sale here:

Met den broeder van laatstgemelden vangt de galerij familieportretten aan. Hij wordt vertegenwoordigd door een flink geschilderd en goed geconserveerd portret van een zestiende-eeuwer, met een langen rossen baard, die met forsche trekken op een papier, onder zijn spreuk Espoir me conforte, een vierregelig fransch vers schrijft, geteekend D. Aellouin 1560. Volgens een opschrift met 17e eeuwsche hand achter op het paneel aangebracht is dit Dirck Alewijn, die volgens de genealogie in 't huwelijk trad met Cornelia Cannius, waarschijnlijk eene bloedverwante van Erasmus

| |

vriend, den geleerden Amsterdamschen priester Nic. Cannius, welke verzwagering echter aan zijne familie nog niet zoo aanstonds den toegang tot het Amsterdamsche regeeringsgestoelte opende, want zijn zoon Dirk Dirksz. Alewijn komt op de Amsterdamsche regeeringslijsten nog niet voor.

|

Translated:

"With the brother of the aforementioned commences the gallery of family portraits. He is represented by a boldly painted and well conserved portrait of a 16th-century person with a long, reddish beard, who with powerful moments writes on a paper, beneath his motto Espoir me conforte, a French verse in four lines, signed D. Aellouin 1560. According to an inscription, from a 17th-century hand, on the back of the panel, this is Dirck Alewijn, who according to the genealogy married Cornelia Cannius, presumably a blood relative of the friend of Erasmus, the learned priest from Amsterdam Nic. Cannius, whose cousinship however didn't immediately open up the Amsterdam government for his family, because his son Dirk Dirksz. Alewijn doesn't appear on the Amsterdam government lists."

Slightly shorter sentences might have made this text more easily understandable, but in any case this again clearly describes the same painting, and gives very interesting information about a text on the reverse, which isn't mentioned by the auction house. Considering that they read the text on the front as "Aetatis. fuce XXXIII" we shouldn't be too surprised about any omissions or errors in the description though...

Anyway, this is about everything I could find about the family, their portrait gallery, and this specific painting. While we don't know who painted it, it is a good work, with a very good provenance now, and I presume that some museum in Amsterdam (the Stedelijk or the Rijksmuseum) would be well interested in adding this to their collection, certainly at the very reasonable estimate.

UPDATE, 15 May 2020; I posted this on Twitter (where I do most of my posts nowadays: only the paintings that need more explanation get the full treatment), and in the ensuing discussion I found some further information, and received some interesting knowledge from art historian Maaike Dirkx, Twitter handle "Rembrandt's Room".

A source I at first dismissed was a "death inventory" of Frederick Alewijn from 1665. I thought Dirck Alewijn was his great uncle and that the paintings described in this inventory were of Fredericks father and grandfather. Maaike Dirkx correctly informed me that the Dirck Alewijn I'm researching here is the grandfather of Frederick, and that the portrait for sale is most likely included in the inventory. The Frick, where I found the inventory, includes the following information: "Frederick Alewijn (1603-1665) was the son of Dirck Alewijn (1571-1637) and of Maria Schurman (1575-1621)." The Dirck mentioned here is the son of the Dirck in the painting (the name reappears many times in their family tree). His brother Abraham Alewijn was a well-known art collector. The inventory includes as #7 "1 conterfeijtsel van Dirck Alewijn" ("1 portrait of Dirck Alewijn"), but is unclear which Dirck this is. But considering that further down in the list we have "2 conterfeijtsels van wijlen Dirck Halewijn met sijn huijsvrouw" ("2 portraits of the late Dirck Alewijn and his wife"), it seems logical that the first painting is of the grandfather (i.e. the painting for sale now), for which there was no accompanying portrait of his wife, and that the other two are the second generation Dirck and his wife. Unless of course #60, "1 mans kontrefeijtsel Dirck Alewijn" is the one here. Most other paintings I show above can be found in that inventory as well, although the portrait of Clara Allewijn is here called one of "cousin de Bij".

There is also an even older inventory, from 1637, showing the possessions of Dirck Alewijn (the son) at the time of his death. It is reprinted on page 54ff. of the 1911 yearbook of Amstelodamum, an institution for the study of the history of Amsterdam. It learns us that the sitter in our portrait is Dirck Dircksz. Alewijn, a "wisselaar" (monet lender) in the Warmoesstraat in Amsterdam (then one of the main shopping streets). He was married to Neeltgen Cornelisdr. and his son Dirck was born in 1571. Because other sources gave the name of his wife as Cannius, I was initially confused and thought that this was a different Dirck. Dirck the son became very rich and had 8 children with Maria Schurman: Clara, Frederick and Abraham were the only three to reach adulthood. Clara is shown in tone of the paintings in this blog post.

In this 1637 inventory, we find a number of paintings which may be of interest for this post (we also find quite a few paintings of general interest for art historians, like a large "Bath of Diana" by Louis Finson or some works by Frans Floris):

UPDATE, 15 May 2020; I posted this on Twitter (where I do most of my posts nowadays: only the paintings that need more explanation get the full treatment), and in the ensuing discussion I found some further information, and received some interesting knowledge from art historian Maaike Dirkx, Twitter handle "Rembrandt's Room".

A source I at first dismissed was a "death inventory" of Frederick Alewijn from 1665. I thought Dirck Alewijn was his great uncle and that the paintings described in this inventory were of Fredericks father and grandfather. Maaike Dirkx correctly informed me that the Dirck Alewijn I'm researching here is the grandfather of Frederick, and that the portrait for sale is most likely included in the inventory. The Frick, where I found the inventory, includes the following information: "Frederick Alewijn (1603-1665) was the son of Dirck Alewijn (1571-1637) and of Maria Schurman (1575-1621)." The Dirck mentioned here is the son of the Dirck in the painting (the name reappears many times in their family tree). His brother Abraham Alewijn was a well-known art collector. The inventory includes as #7 "1 conterfeijtsel van Dirck Alewijn" ("1 portrait of Dirck Alewijn"), but is unclear which Dirck this is. But considering that further down in the list we have "2 conterfeijtsels van wijlen Dirck Halewijn met sijn huijsvrouw" ("2 portraits of the late Dirck Alewijn and his wife"), it seems logical that the first painting is of the grandfather (i.e. the painting for sale now), for which there was no accompanying portrait of his wife, and that the other two are the second generation Dirck and his wife. Unless of course #60, "1 mans kontrefeijtsel Dirck Alewijn" is the one here. Most other paintings I show above can be found in that inventory as well, although the portrait of Clara Allewijn is here called one of "cousin de Bij".

There is also an even older inventory, from 1637, showing the possessions of Dirck Alewijn (the son) at the time of his death. It is reprinted on page 54ff. of the 1911 yearbook of Amstelodamum, an institution for the study of the history of Amsterdam. It learns us that the sitter in our portrait is Dirck Dircksz. Alewijn, a "wisselaar" (monet lender) in the Warmoesstraat in Amsterdam (then one of the main shopping streets). He was married to Neeltgen Cornelisdr. and his son Dirck was born in 1571. Because other sources gave the name of his wife as Cannius, I was initially confused and thought that this was a different Dirck. Dirck the son became very rich and had 8 children with Maria Schurman: Clara, Frederick and Abraham were the only three to reach adulthood. Clara is shown in tone of the paintings in this blog post.

In this 1637 inventory, we find a number of paintings which may be of interest for this post (we also find quite a few paintings of general interest for art historians, like a large "Bath of Diana" by Louis Finson or some works by Frans Floris):

- "Vier contrefeytsels van grootvader grootmoeder moeder en kint" (four portraits of grandfather, grandmother, mother and child); without further specification, so probably not family members but some generic paintings

- "Tcontrefeytsel van sa. Dirick Alewyn ’" followed by "Tcontrefeijtsel van J&r. Eva Stalpaert", so this is probably a portrait of Dirck the son paired with one of his second wife, and not the painting for sale here, nor the painting of his son shown above (since that one was paired with one of his first wife)

- "Tcontrefeytsel vande Raetsheer Reynier Pau en sijn huijsvrou en soon en dochter elc apart" = portrait of council member Reynier Pau and his wife, and son and daughter each separately. The first two are shown in this blog post.

- "Tcontrefeytsel van Joannes Canenius en sijn moeder elck apart", or the portraits of Joannes Canenius and his mother, separately: as the commentary in this article indicates, the fact that paintings of the Canenius or Cannius family are in this inventory show the relation between Dirck Alewijn the Elder and this one

- "Tcontrefeijtselvansa: DiricAlewijn ’ Tcontrefeytsel van sa: Maria Schuijrmans ’" This is probably the painting shown in this blog post, and the one lost in the fire

Strangely, the painting for sale is not (clearly) included in this inventory. Perhaps at the time it belonged to another member of the family, or it is misidentified (here or later) as e.g. the portrait of Joannes Canenius.

Finally (for now at least), I also found another mention of the work for sale in a Dutch literary magazine from 1866, "De Navorscher", where a certain P. Opperdoes Alewijn, a direct descendant of the family, gives a lot of information about his ancestors. The parents of Dirck Dircksz Alewijn (the subject of the portrait for sale) were supposedly Diderick de Haleuin, ennobled for services to the Frech King François I (king between 1515 and 1547) and Anna Cannius. How it is explained that both father and son married a Cannius wife is not clear. In any case, it continues with:

Dczo Diderick De Haleuin, gehuwd met Anna Kan' of Cannius, had twee zoons (van meer kinderen is niets opgeteekend).

1°. Dirck Dsz. Alewijn, geboren 1527, gehuwd geweest met Cornelia Kan of Cannius, zijnde de voorvader van den oudsten tak, waartoe ik behoor. Ook bezit ik van hem een portret in olieverw, waar hij is afgebeeld zittende aan eene tafel met een schrijfpen in de regterhand; voor hem ligt een stuk papier op hetwelk zijn linkerhand rust en waarop een moeilijk in zijn geheel te lezen vierregelig versje door hem geschreven is, tot hoofd hebbende de woorden »Espor me conforte;" wijders voorzien van zijne naamtcekening D'alleuin en het door hem gestelde jaartal 1560. In den regter bovenhoek op de schilderij leest men ./Etatis XXXIII.

Translation: "This Diderick de Haleuin, married to Anna Kan or Cannius, had two sons (more children aren't mentioned).

1° Dirck Dsz. Alewijn, born 1527, married to Cornelia Kan or Cannius, is the forefather of the elder branch, of which I'm a member. I also possess of him a portrait in oil, where he is depicted sitting at a table with a writing pen in his right hand: in front of him is a piece of paper upon which his left hand rests, and on which a small poem of four lines, hard to read completely, has been written by him, headed by the words "Espor me conforte", further bearing his signature 'Alleuin and the year 1560 stated by him. In the upper right corner of the painting one can read "Aetatis XXXIII"

So, yet another clear indication that this exact painting was owned by the family in the 19th century, and believed by them to be their first ancestor.

This is of course the advantage of finding a portrait of a member of an old, rich family which remained active for a long time and kept on to their possessions and papers; it makes it so much easier to find lots of information, even just by looking online.

UPDATE 2, 18 May 2020: I haven't been able to access it, but the 1885 auction also had an auction catalogue printed, and one copy of this is in the possession of the Rijksmuseum, so perhaps further information (like the exact dimensions, or about the text on the back) can be found there. If we're very lucky, it also contains the name of the buyer and the price it fetched.

The snippet view in Google (no idea if this was taken from the Rijksmuseum copy or not) seems to show someone having transcribed the four-line poem, so that as well would be nice information to have.

UPDATE 2, 18 May 2020: I haven't been able to access it, but the 1885 auction also had an auction catalogue printed, and one copy of this is in the possession of the Rijksmuseum, so perhaps further information (like the exact dimensions, or about the text on the back) can be found there. If we're very lucky, it also contains the name of the buyer and the price it fetched.

The snippet view in Google (no idea if this was taken from the Rijksmuseum copy or not) seems to show someone having transcribed the four-line poem, so that as well would be nice information to have.

UPDATE 3: sold for 5816 Swiss Francs, so near the top of the estimate, but a good price for this painting with lots of history.

Wednesday, 18 March 2020

What's with the many artists making still lifes with blue ribbons?

Schlosser, from Germany, sells on 27 March 2020 as lot 19 a "Flemish Master, 17th or 8th century" still life, estimated at 3,000 Euro.

It is an attractive work, which looks well painted: but the image is not good enough to be certain, and it looks somewhat overcleaned as well. If you would like to bid on it, best to ask for better images first. For my blog I like to base myself solely on what the auction houses present online though.

It seemed easy enough to search: while there have been countless good still life painters, the use of such a distinctive blue ribbon should narrow it down considerably. And indeed, I soon came across Cornelis de Heem (1631-1695), who used this device repeatedly. The above example, from Bowes Castle, also has it combined with grapes, so now I only had to look a bit more in detail to see if it would be a work by him, from his workshop, a follower, ... and then to decide the value.

I found other works in the same vein by De Heem, like this one offered at Lempertz with a 30,000 Euro estimate, or another one from the V&A.

But that further look also showed me works by Christiaan Luyckx, Joris Van Son, Laurens Craen,...

And then I start looking for details which are even closer to the work for sale. Isn't the ribbon rather similar to the one in this work by Pieter Gallis (Christie's, sold for £27,000)? Well, it's closer than the other ones, but the material seems different, and the remainder is also too pale to be comparable to the (too?) warm colours in the work for sale. Other details can be matched to other artists and works, like the opened pomegranate (De Heem and Luyckx for example).

So I have to step away from my favourite method, looking for similar compositions, elements, ... and focus a bit more on the tricky subject of style. And to me, among the many late 17th century artists in Flanders and the Netherlands using this device, the closest is Maria van Oosterwyck (1630-1693), one of those 17th century women artists who were easily the equal of most male painters, but were too long forgotten (or at least ignored).

She was a student of Jan Davidsz de Heem, the father of, yes, Cornelis de Heem. Oosterwycks work is characterized by bright, strong colours, shining out against the dark background. The main difference is that Oosterwyck usually painted flowers, not fruit, but there turn out to be some works by her combining grapes and a blue ribbon after all.

Bonham's sold a work for £56,000 in 2013. I have added a detail from the work for sale below it, for comparison.

Another one, with grapes, was sold by Christie's in 2003 for £20,000.

The RKD lists a similar one which was for sale with Richard Valls.

So, is it an Oosterwyck painting? I would love it to be, but I'm not convinced. A "Circle of Cornelis de Heem", that's for sure, but anything more precise than that is, based on the not-so-good painting and my limited knowledge, just guesswork. Still, it seems an interesting work for its price, it introduced me to the omnipresent blue ribbon in these works, and perhaps someone else will know who painted this.

It is an attractive work, which looks well painted: but the image is not good enough to be certain, and it looks somewhat overcleaned as well. If you would like to bid on it, best to ask for better images first. For my blog I like to base myself solely on what the auction houses present online though.

It seemed easy enough to search: while there have been countless good still life painters, the use of such a distinctive blue ribbon should narrow it down considerably. And indeed, I soon came across Cornelis de Heem (1631-1695), who used this device repeatedly. The above example, from Bowes Castle, also has it combined with grapes, so now I only had to look a bit more in detail to see if it would be a work by him, from his workshop, a follower, ... and then to decide the value.

I found other works in the same vein by De Heem, like this one offered at Lempertz with a 30,000 Euro estimate, or another one from the V&A.

But that further look also showed me works by Christiaan Luyckx, Joris Van Son, Laurens Craen,...

And then I start looking for details which are even closer to the work for sale. Isn't the ribbon rather similar to the one in this work by Pieter Gallis (Christie's, sold for £27,000)? Well, it's closer than the other ones, but the material seems different, and the remainder is also too pale to be comparable to the (too?) warm colours in the work for sale. Other details can be matched to other artists and works, like the opened pomegranate (De Heem and Luyckx for example).

So I have to step away from my favourite method, looking for similar compositions, elements, ... and focus a bit more on the tricky subject of style. And to me, among the many late 17th century artists in Flanders and the Netherlands using this device, the closest is Maria van Oosterwyck (1630-1693), one of those 17th century women artists who were easily the equal of most male painters, but were too long forgotten (or at least ignored).

She was a student of Jan Davidsz de Heem, the father of, yes, Cornelis de Heem. Oosterwycks work is characterized by bright, strong colours, shining out against the dark background. The main difference is that Oosterwyck usually painted flowers, not fruit, but there turn out to be some works by her combining grapes and a blue ribbon after all.

Bonham's sold a work for £56,000 in 2013. I have added a detail from the work for sale below it, for comparison.

Another one, with grapes, was sold by Christie's in 2003 for £20,000.

The RKD lists a similar one which was for sale with Richard Valls.

So, is it an Oosterwyck painting? I would love it to be, but I'm not convinced. A "Circle of Cornelis de Heem", that's for sure, but anything more precise than that is, based on the not-so-good painting and my limited knowledge, just guesswork. Still, it seems an interesting work for its price, it introduced me to the omnipresent blue ribbon in these works, and perhaps someone else will know who painted this.

Tuesday, 17 March 2020

Flemish "Lamentation": many copies, where's the original?

Schlosser, from Germany, sells on 27 March 2020 as Lot 3 an "Early Netherlandish Master, 2nd half of the 16th century" Lamentation, estimated at 4,500 Euro.

This composition exists in many versions, but there doesn't seem to be an actual original. It does hark back to a Joos van Cleve composition now in the Städel in Frankfurt, as the RKD notes, but some intermediate step is missing to explain how all these poorer copies made the exact same changes (e.g. in the position of the head of the Virgin).

Most copies are somewhat closer to the Cleve in the figure of the Magdalen on the right: in the work for sale, this has been modernized somewhat, and perhaps this version must be dated closer to 1600 than the others.

The two anonymous versions from the RKD show how much closer these are to the one for sale than to the Cleve. The first one was sold at Sotheby's in 2010, the second one was with art dealer Van der Lubbe in The Hague in 1941

Another version was for sale with Promenade Antiques, as "circle of Van Cleve, ca. 1530". All these versions have a "table" or similar in front of the Christ, with elements of the Passion; the one or sale has lost this aspect.

A very nice version was sold at Sotheby's in 2012 for $8,750 Euro, good value for money there. it is very close to the two RKD examples, but better executed.

The one for sale will probably struggle to meet expectations, as it is not the best copy, and slightly later than hoped for.

This composition exists in many versions, but there doesn't seem to be an actual original. It does hark back to a Joos van Cleve composition now in the Städel in Frankfurt, as the RKD notes, but some intermediate step is missing to explain how all these poorer copies made the exact same changes (e.g. in the position of the head of the Virgin).

Most copies are somewhat closer to the Cleve in the figure of the Magdalen on the right: in the work for sale, this has been modernized somewhat, and perhaps this version must be dated closer to 1600 than the others.

The two anonymous versions from the RKD show how much closer these are to the one for sale than to the Cleve. The first one was sold at Sotheby's in 2010, the second one was with art dealer Van der Lubbe in The Hague in 1941

Another version was for sale with Promenade Antiques, as "circle of Van Cleve, ca. 1530". All these versions have a "table" or similar in front of the Christ, with elements of the Passion; the one or sale has lost this aspect.

A very nice version was sold at Sotheby's in 2012 for $8,750 Euro, good value for money there. it is very close to the two RKD examples, but better executed.

The one for sale will probably struggle to meet expectations, as it is not the best copy, and slightly later than hoped for.